I’ve been wanting to start a series of articles about great long hikes for a long time, so here goes. And if you’re going to talk about long hikes, then as far as I’m concerned, you HAVE to start with the Appalachian Trail. It’s the great-granddaddy of the long-distance hiking movement, coming up on a century old, and it has an iconic status in the hiking world that is, quite simple, unassailable.

|

| Maine’s Mighty Katahdin, the Northern Terminus |

Let’s get the numbers out of the way.

- 14 states (from Georgia to Maine).

- It takes between 4 and 6 months to hike the whole thing, depending on how fast you go.

- As of today’s writing, according to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, which manages the trail, 11,823 people have completed the entire trail from end to end.

- The youngest was a six-year old boy; the oldest a 71-year old woman (An 80 year woman is the oldest section hiker; ie, person to complete the entire trail in a series of sections hiked over several years).

- Approximately 25 percent of thru-hikers are women.

- The trail encompasses some 250,000 acres of public land.

- It runs for nearly 2,200 miles. (The precise length keeps changing due to slight locations to move the trail to better routings as they become available through easements, or to respond to storm damage.)

What is interesting to me is the head-and-shoulders dominance of the Appalachian Trail as a long-distance hiking destination. Since 2000, Some 600 hikers a year complete the trail — out of 2,000 – 3,000 starters. Compare this to the several hundred to who attempt the Pacific Crest Trail — and the few dozen who actually succeed. The ATC estimates that some 2 – 3 million people hike on the trail each year, making it one of America’s most popular national parklands.Yet you can still find yourself totally alone with nature.

There’s no question that other trails are higher, have more stunning scenery, spend more time above treeline, have more variety… but it’s the AT that draws the hikers.

Appalachian Trail Basic Geography and Terrain

A few points about the AT if you’re considering hiking a chunk of it. (And thru-hikers: Check this article about basic Appalachian Trail thru-hiking information; it’s the beginning of a series for thur-hikers):

The trail can be roughly divided into four sections: The South (Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee), Virginia (along with West Virginia and Maryland), the mid-Atlantic states (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York), and New England (Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine).

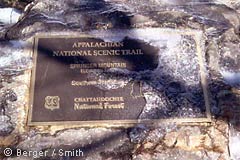

|

| Southern Terminus Marker at Springer Mountain |

The South has the highest mountains (although none of them poke above treeline, as they do in New Hampshire and Maine), along with a variety of terrain, from easy rambles to straight up and down scrambles. The Great Smokey Mountains National Park is a good starting point for beginners, with a combination of well-marked and maintained trails and spectacular mountain landscapes.

Virginia is possibly the easiest of the four sections, with sections of trail that are downright gentle. Thru-hikers typically hike about 20 miles a day here (or more).This section’s highlights in include Shenandoah National Park and the Mt. Rogers, which has dramatic open mountain terrain and wild ponies.

|

| The “Long Green Tunnel” |

The mid-Atlantic section may be where the trail got its nickname, the “Long Green Tunnel.” But although the elevations are low, that doesn’t necessarily make for easy trail: Pennsylvania is called “Rocksylvania” because of the rocky glacial debris left all over the place. The New Jersey section is surprsingly wild and beautiful: It starts at Interstate 80, and immediately climbs past lovely Sunfish Pond, which is a glacial tarn. The trail then hugs ridges covered with mountain laurel. New York boasts the oldest miles of trail, in Bear Mountain State Park, and the lowest elevations (at the Bear Mountain Zoo), but there are lots of what hikers call “PUDs” (pointless ups and downs; for more thru-hiker lingo, check out the AT lingo post) which add up to enormous elevation gains and losses.

|

| Autumn in New Hampshire |

In New England, the trail just gets prettier and prettier. The Connecticut and Massachusetts sections are varied, from the riverbeds of the Housatonic to the rocky outcrops of the Berkshire ridges. In southern Vermont, the AT is contiguous with the Long Trail before it veers east to new Hampshire and Maine where the trail finally breaks free on treeless mountain summits, navigates hiking trail that at times resembles rock climbing more than hiking (mileage goes WAY down here), then ambles through Maine’s so-called “100-Mile wilderness” and ends in glory atop Katahdin.

A Community in the Wilderness

|

| An Appalachian Trail Shelter |

If the Appalachian Trail were merely all that… the long mileage, the 14 states, the thousands of mountains … it would be remarkable, but there is another aspect to it: The trail community, which encompasses the thru-hikers, the day-hikers, the weekenders, the volunteers, the managers, the townspeople, the hostel owners, the shelters where hikers cluster together, and the hiking alumni who show up for trail festivals or to dispense a bit of ‘trail magic” — taking hikers home, giving them a bit of a trail vacation.

And all this takes place within a few hours’ drive of most of the East Coast metropoli. You can actually see New York City from the trail (atop West Mountain, in New York), and take a train in on the commuter line, which stops at the eponymous Appalachian Trail station. Benton MacKaye, the trail’s founder, envisioned the trail as a place for respite, recreation, and rejuvenation from a American’s increasingly urban environment. He envisioned communities visiting these rural areas, linked by a trail: staying a farms and in the forests, creating a sort of wilderness community. His utopian vision didn’t quite come to fruit as he intended, but instead morphed into a trail community that in its own way does what he envisioned: provide a chance to reconnect with nature in a profound and rejuvenating way.

And that, I think is the crux of what makes this trail so special. The number of people who hike it, the volunteers who maintain it, the trail shelters where hikers gather and sleep, the trail festivals that have sprung up in communities along the route: All of these have created something more than a mere hiking trail. The AT is a community in the wilderness: Two ideas that don’t go together.

Biologists tell us that the richest areas in an ecosystem are the places where two different types of communities come together: forest and marsh, lake and prairie, sand dune and salt marsh. In such places, ecological communities support the species of each overlapping ecosystem, as well as a few species unique to the intersection. That, I think, is the magic of the Appalachian Trail: In the juxtaposition of community and wilderness, we find something unique: part wild, part civilized — and entirely magical.